Black Box (2013)

Theseus (1950), Claude Shannon’s mouse, showed us the possibilities of artificial intelligence (AI). An electronic mouse, Theseus, navigates its way around a maze to a predesignated target and, once completed, has the ability to recall the route to the target from any place in the maze.

To understand the AI of the mouse (or indeed the programmer of the AI mouse) as autonomous is a misconception: it is in fact Shannon, the creator of the maze and he who determines the mouse’s place within the maze, who holds the autonomy. The freedom of Theseus is limited by what options are available to it within its situation, and acts accordingly from a set of predetermined choices.

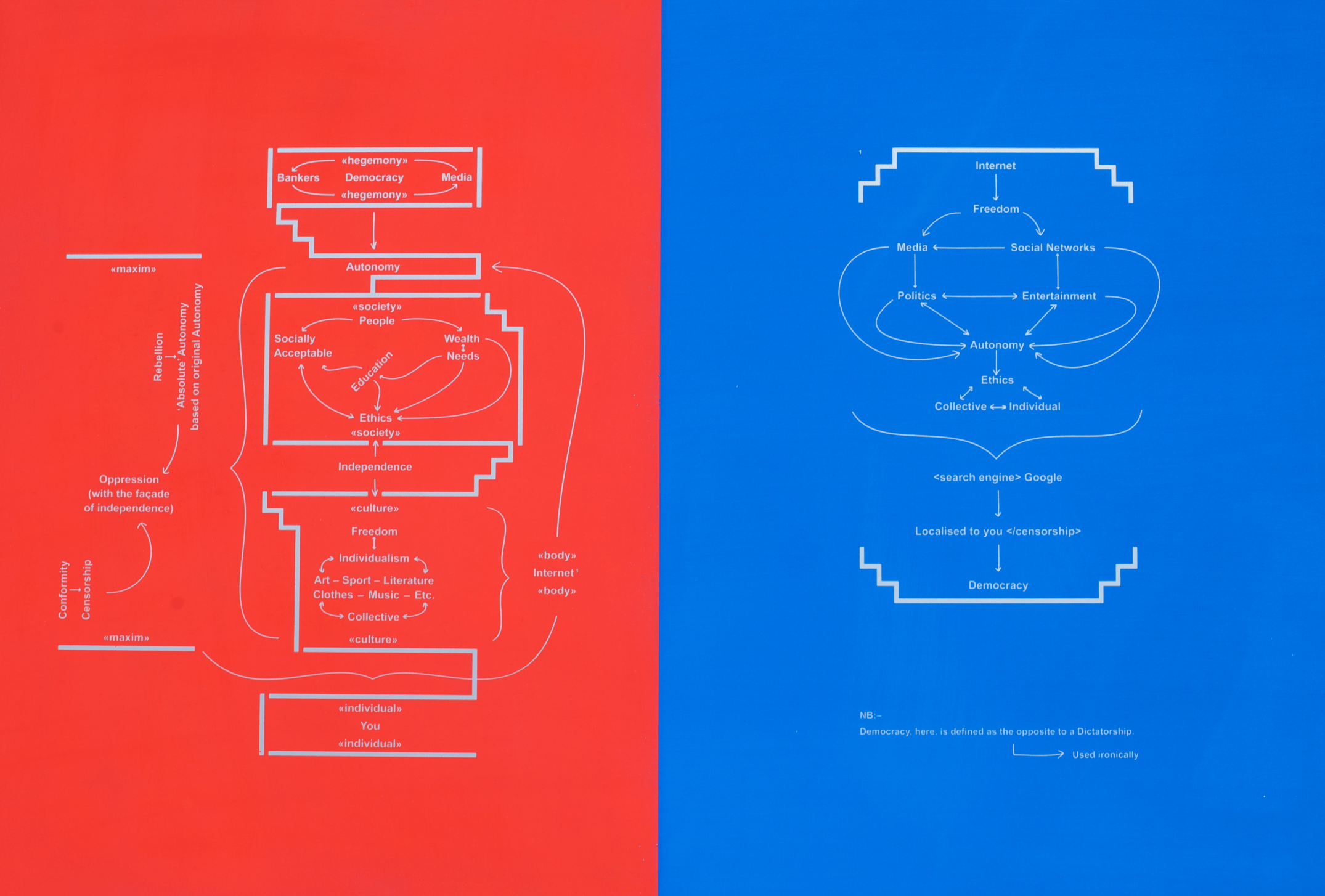

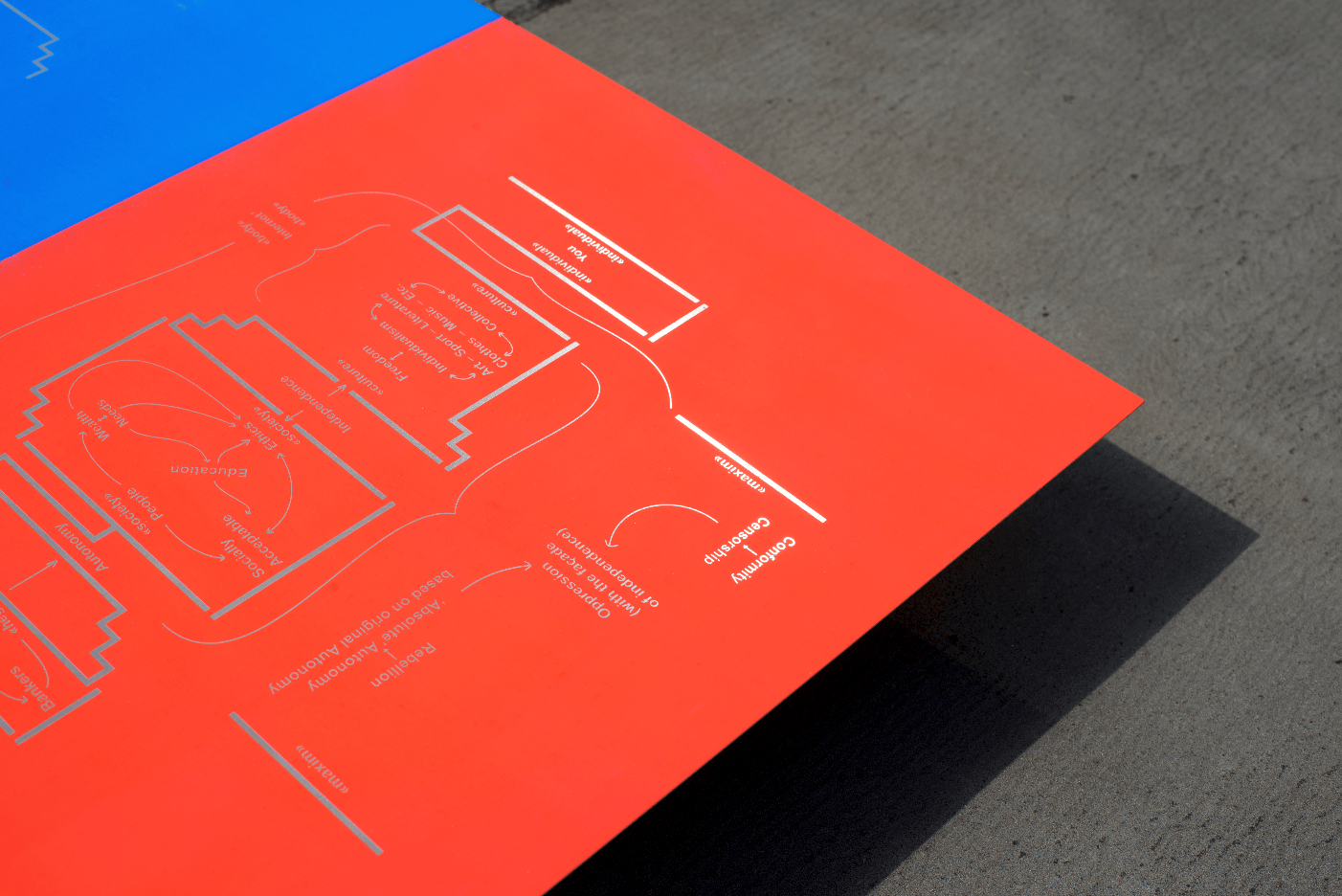

In the 21st Century, how different are we to Theseus? We have agency over which route we may take, but we never made the decision to be placed in this maze. We are thrust into the world with our final destination already determined. There are a few key milestones – school, a job, marriage, retirement – all of them chosen for us before we are born, and we, like Theseus, have the freedom to make decisions, but we do not create the maze that is society.

Positive Law (2011)

We label predetermines limitations as ‘rights’.

The illusion of autonomy allows for a misplaced notion of happiness. The achievement and fulfillment of one’s moral and values enable the individual to call themselves happy. When one achieves a certain degree of fulfillment against the moral and value-based prescriptions within the maze, we are able to call ourselves happy. This is fundamentally beset by certain parameters.

The laws that govern our life are Positive Laws, that is to say: they are man-made laws which oblige or specify an action. They describe the establishment of specific rights for an individual or group, predicated upon the notion of promoting happiness, peace, and order. Rather, it creates a simulation of happiness, where having these rights creates an administered structure of happiness, where the success or failures one has within this scaffolding are secondary. A prime example of this would be the American Dream.

Any man-made laws which we mistake for natural laws have a blurring effect, masking the distinction between true and false happiness. Is the creation of a set of laws, without the consent of those who will involuntarily abide by them, the purest form of censorship? Consider modern surveillance culture to ensure participation and the result is something shockingly akin to the depictions of dystopia in Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World” and Dave Egger’s “The Circle”.

To monitor an individual all one needs is that individual’s appearance and name. Once we have those two pieces of information, the individual’s identity belongs to the state. Bank accounts, passports, mortgages, driving licenses, even a library card: all of these things are dependent on our image and name.

There is nothing more personal than this information, and yet we readily give it away. The right to privacy and anonymity – the right to give your information only to those who you know and trust – has been rendered non-existent. We can keep our identity personal, but it is instilled in us from a very young age that to reveal is natural. To reveal is to turn yourself into a statistic for those that govern. To reveal negates the difference between Theseus and ourselves.

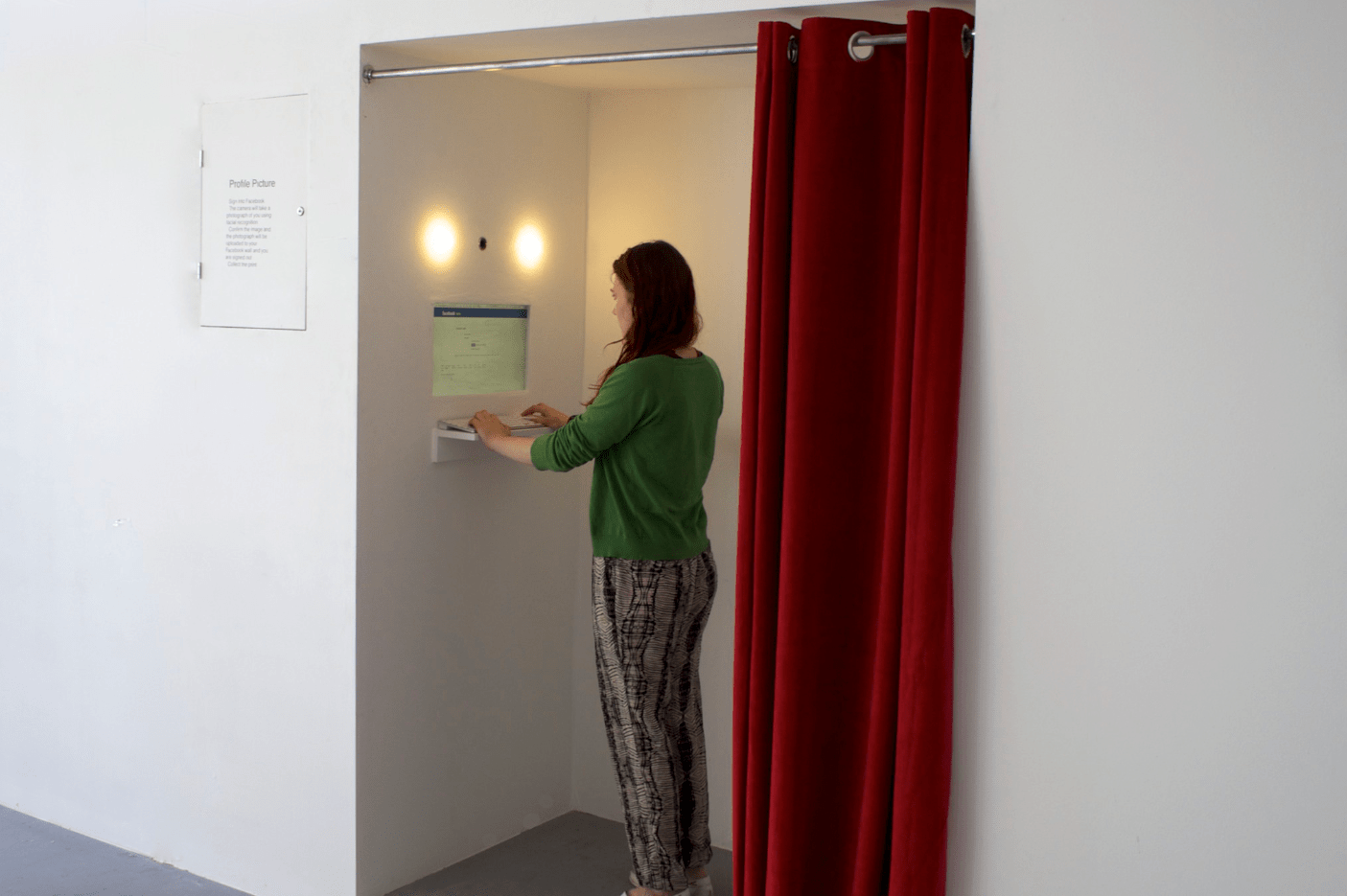

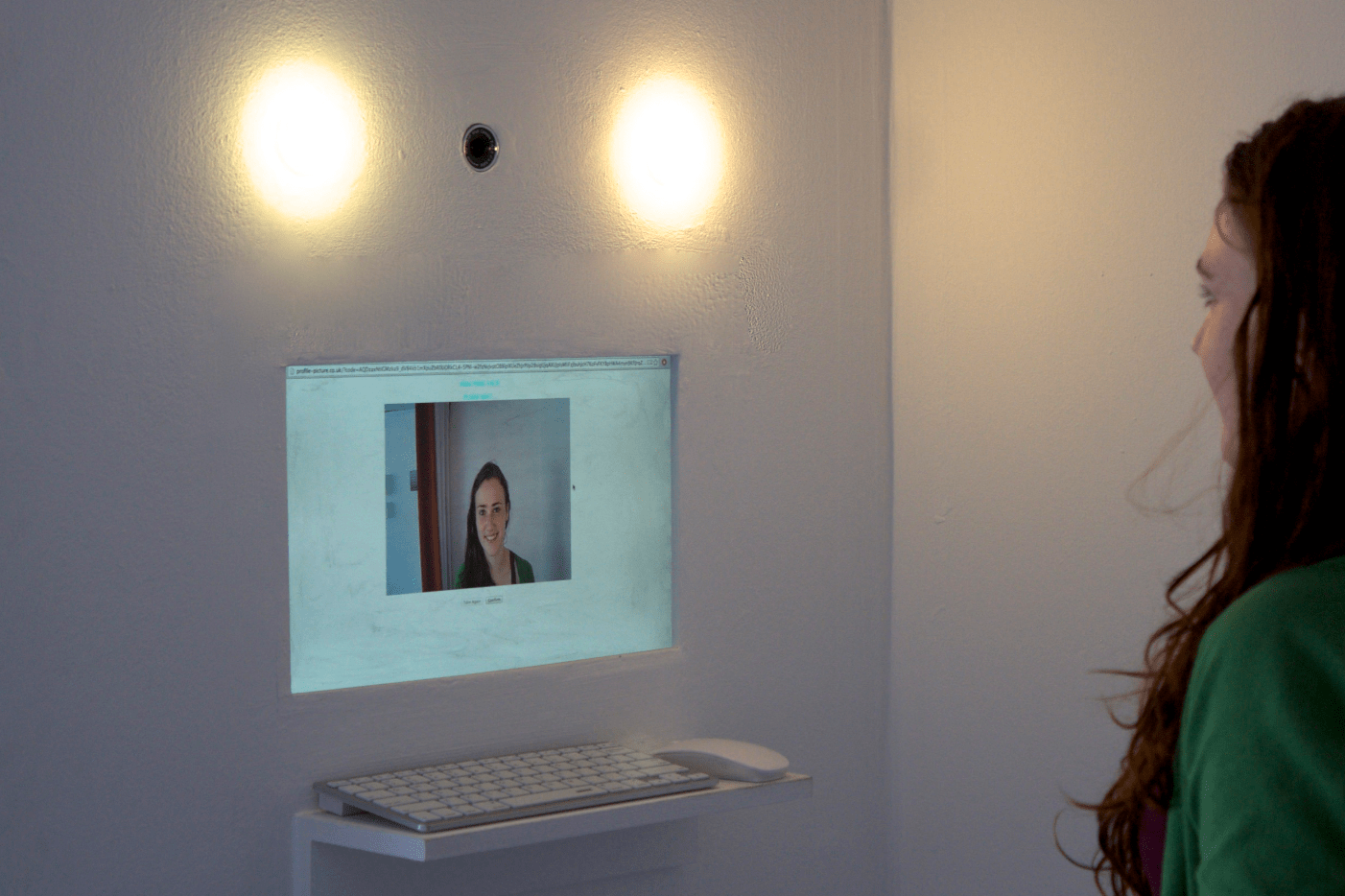

Profile Picture (2014)

Conformity is misinterpreted as individuality.

One’s right to image and name is one which has been left behind. One’s name and image alone are what can trace anything and everything back to you in the physical world. There are obvious constraints on the extent to which one can reserve the right to the privacy of their image, but the few things you can do are slowly being made illegal or socially unacceptable. In 2010, France ‘prohibited [the] concealment of the face in public space[s]’. This was a gesture by no means made in a political or social vacuum, and France does bear a markedly chequered relationship with religious – particularly Islamic – practice. However, to view things structurally, the end result is that the right to conceal or mask one’s face is taken away.

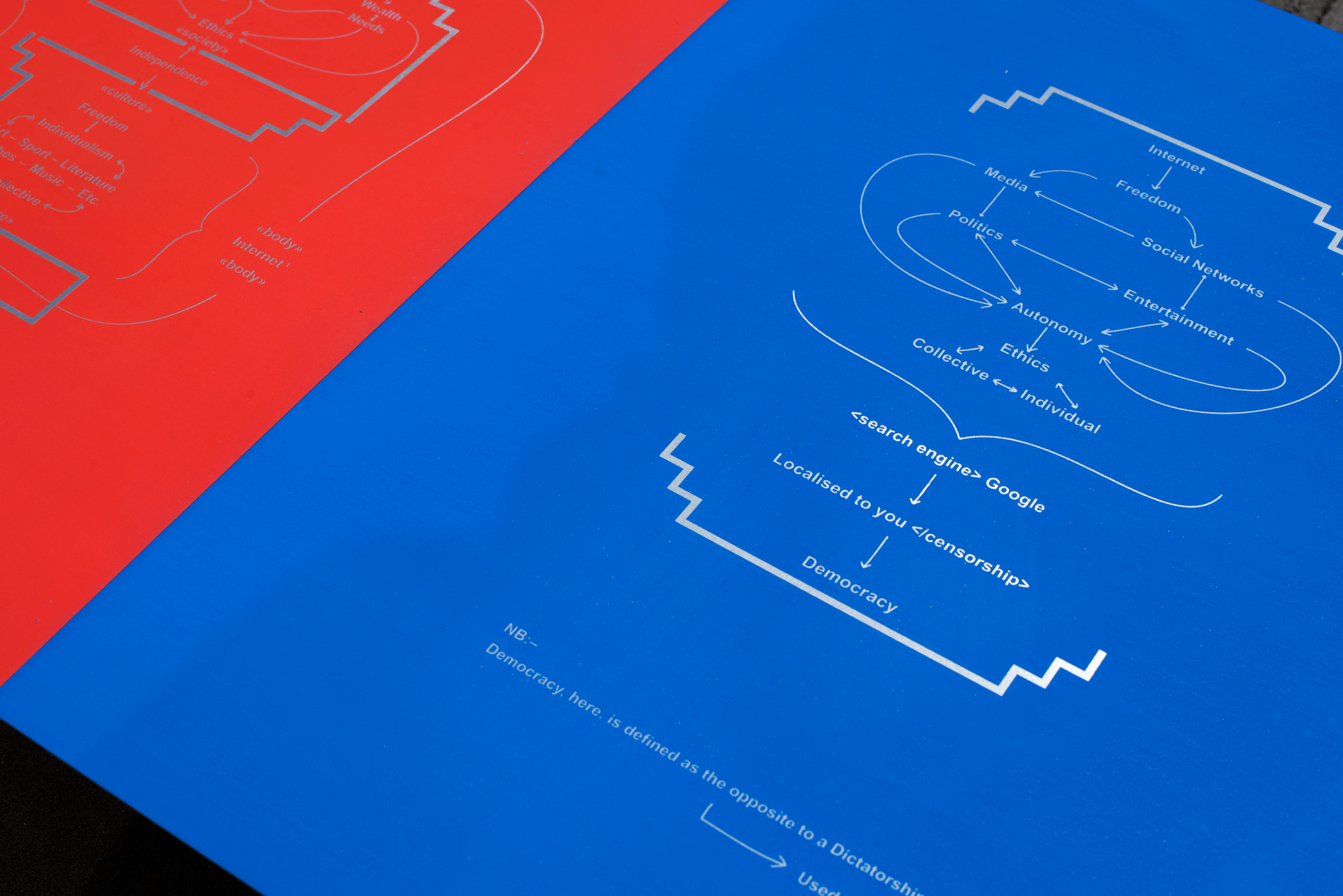

The veil once used to mask one’s identity in public spaces, had long since been removed in private spaces, with the interception and surveillance of our locations, messages and thoughts, through the tracking of the usage of electronic devices. We are more honest with Google than we are with any person: we Google our problems, whatever they may be, as well as what we like, what we want to know, what we’re planning on doing, our thoughts – everything. We talk to our friends and family through Facebook and Gmail, and we constantly update our image, our preferences, our interests, and our movements. All of this, amongst much, much more information - as we’ve all known for some time - is monitored.

‘But what does it matter? I’ve got nothing to hide.’

Besides the unhelpfully principled and abstract answer of, ‘because we have a right to privacy,’ there doesn’t seem to be much of a rebuttal to statements such as this. The right to privacy is a natural law - since the ability of privacy is something that has been taken away - that has been impinged upon us by Positive, man-made laws. When the individual’s personal information is sold to advertisers, issues start to become consolidated. Advertising does not equate to increased commercialisation of existing commodities in the realm of social media, but it commodifies things such as thoughts, opinions, and ways of life. Advertising is a form of propaganda, an element continually disassociated with the word.

Advertising, like Google, localises information to the individual. This can be very helpful and useful, but also very limiting and restrictive. This means that the individual is restricted to seeing and learning only what the facilitator of this tailored algorithm (in this instance, Google) decides they can see. The ingenuity of its faith in laziness, combined with its correct predictions, allows us to believe that we have the autonomy to select what we see freely, since Google opens up so many more opportunities in the pursuit of knowledge. In reality, it is necessarily Google (and advertisers) who dictate what is made available for us to see, learn and indeed what we want to learn. When we hear certain music, read particular news, we form opinions and seek further knowledge based on this seeding of information.

We are not free to become who we want to be, yet the fabric of this oppression is hidden behind a façade of greater-than-ever-before potential for individualism, greater freedom and greater knowledge. Within this particular maze, crafted by Mark Zuckerberg, Eric Schmidt, Jeff Bezos, and myriad other, far less public figures, our individual selves are commodified. Our information is bought, used, and sold, and our individual identities are eroded.

Facebook has grown from being a tool for communication into something far larger and more powerful, as the Internet centralises. Our Facebook accounts work like social passports. We provide current photographs, our date of birth, locations, friends, interests and much more personal information. Our every action, thought, and private conversation is documented and stored.

Our online presence acts as a window into our lives, appealing to a carefully cultivated narcissism more and more present within human psychology. Facebook’s genius is not in its communication (though it does this very well), rather, in its model of feeding. It grows from knowledge of humanity, which it gains through our use of it. It is a self-feeding machine, its tool for growth the end result of its offering.

Facebook knows all too well the psychological process which occurs when someone uploads a photo of you, tags you in a status, or posts something on your wall. The narcissistic thirst for public approval and acknowledgement is wrapped in a little package for you to open. At the same time, information about you is being shared to others, and everyone revels.

Facebook has turned everyone into a celebrity. The feeling that others are jealous of us is addictive, as is the jealousy we feel of others as we see them in picture and cannot not make instant comparison with them. Thus, we provide more information, lodge more interests, grow our network of friends, upload more pictures, as we become socially and culturally dependent on this new platform, all the while providing Facebook the endless stream of data it needs to grow more powerful and cement its intransigence to the 21st Century individual and societal foundations.

Personal data is arguably the most valuable collective information there is. The more likes, social interactions and following you have, the more sway you have and the more valuable you become to advertisers. Those with less sway or followers, become the product as their newsfeed is adapted to mirror not only the interests of the individual and society, but rather the interests of the individuals with a bigger influence – who in turn are influenced by what advertisers and the social and political agenda of the Social Media site desires. Advertisers regularly buy posts made by individuals, and ensure that it crops up on your and your friends’ walls if it mentions the product of the advertiser or if it is of appropriate relevance.

We alter our choice in actions because of the documentation of our activities on Facebook. At this point, our actions become artificial and driven by the social media platform rather than the pursuit of genuine gratification: at this point, Facebook has altered the parameters by which you can get the validation from others to call yourself happy.

As mimetic animals, it is easy to disseminate an idea of happiness, controlled and defined by Facebook and advertisers in which they do business with. We start using particular words and phrases, we learn the structure of Facebook which allows the desired effect: to make us look the most attractive to our friends and sexual partners. We form, grow, and destroy friendships – all of which take place in an arena where everything exists publicly through documentation, and the way in which we interact, both online and off, are defined by the medium.

Our projected identities have been given a concrete podium with the creation of Facebook. The distinction between who you are and who you want to be can cohabit online, and when the structure of Facebook necessarily breeds conformity, taking contrived outward appearances as the basis for interaction, then we have a society in which individuality is replaced by conformity, where our idiosyncrasies become endearing novelties.

A recent BBC report state that 79% of 10-12 year olds have a Facebook account in the UK, with some as young as four also having personal accounts, (you must be 13+ to have a Facebook account), with the need to have one ascribed to the desire ‘to fit in’ with others, and ‘not be different’.

There is a social standard for how Facebook should operate. In the physical world, we are influenced by social and legal law. Our Facebook selves are no different – but are also limited by the very structure of the platform itself. Despite the potential freedom the Internet promised, the centralisation of the world wide web has meant that these limitations are far more restrictive than those of the physical world.

Facebook has allowed us to create an image of ourselves which we perceive to be the most outwardly appealing. We choose the most attractive photographs of ourselves, we choose to say things which we think others will like. We align ourselves with some and distance ourselves from others, without the difficulty and commitment required to do so in physical society. We can mould our online personae into whoever we want ourselves to be while remaining, on the other side of the screen, Joe Bloggs from Leicester, born in the early ‘90s, and yet, our image of who we want to be is standardised to the norms of every other Facebook Account user, and where different, is defined in being different in reaction to the social norms which Facebook has bred.

Our prescribed virtual identity is seeping into the physical world: there is necessarily a very murky line between the two, and ramifications are forced to cohabit. The US government have denied access to people based on posts made on social media sites, and on some occasions Facebook Accounts have quite literally acted in lieu of a passport. In December 2013, Zach Klein boarded a plane with only his Facebook Profile in place of his passport when he left his passport elsewhere. Passports have carried with them a character profile since 1915 in Britain, and what Facebook allows is for the most detailed and vivid account of a person’s character – and/or the projected ideal of one's character.

Our online passport is becoming the standard. But our prescribed identities are subject to the restrictions which Social Media companies puts in place, and that coupled with the evolution of data mining, analysis and the autonomy to decide what is seen or not, is adding up to a world in which we maintain only a very fragile grip on the self which we believe to be inherently our own. We don’t own the profile or passport: Facebook owns all of the information posted on it. We merely borrow it. We cannot delete it, or ever alter archived information. Facebook owns our projected personae, and Facebook owns our biggest insecurities.

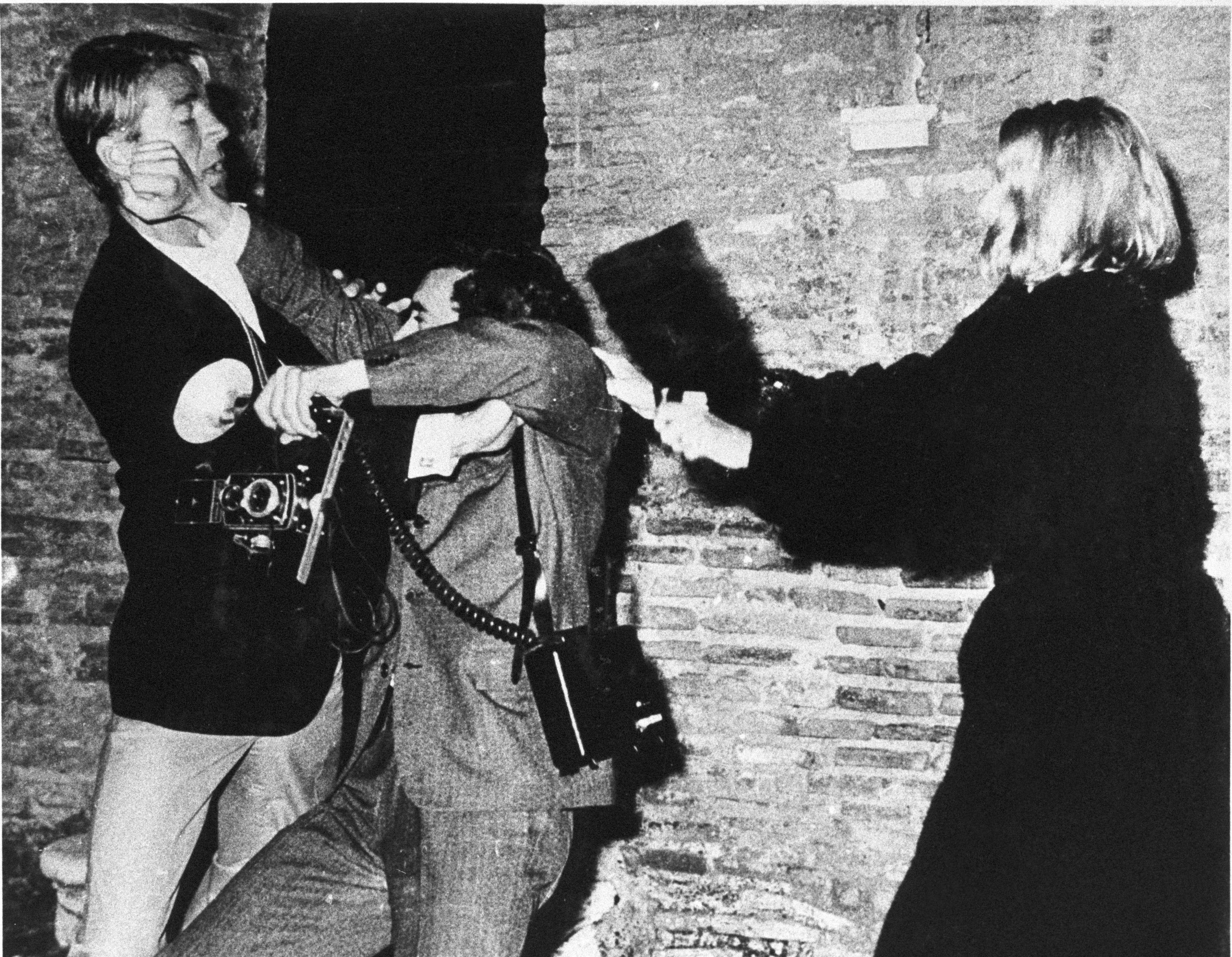

One Wrong Makes a Wrong (2013–2014)

How in control are any of us?

I am a paparazzo. I scour social media profiles, gossip columns and websites. I wait for celebrities to come out of their house, car, restaurant, or club. Anywhere. I bide my time, get the shots, and upload the most valuable to a website. From the point at which I take the photographs to the time at which they are bought by newspapers there are almost fifty identical images uploaded by other paparazzi. That’s three minutes. It’s a competitive business – the images of celebrities are in very high demand.

My take is 60% of what the image sells for and the company takes the remaining 40%. Photos go for between £50 and £80,000.

I never sold an image because I never uploaded one to the site. I did, however, become the agent of a co-owner of one of the largest paparazzi companies in the UK, and then turned the lens on him. I became the paparazzi’s paparazzo.

I will tell you one thing about this person (X): he is male.

Once I had decided who the most viable target was, Facebook was my first port of call. I spent almost five boring and intrusive months ‘Facebook stalking’ him, and was able to glean a few key facts. I found out his date of birth, area of residence, education history, his friends past and present, the places he liked to spend time, his interests, his car, his registration, and the identity of his girlfriend. Via the same means, I was able to find out the above information for all of his friends and their friends and partners.

To find someone’s address, all you need is a name, a rough area of residence, and a website. From there you can find out the exact address, who else is resident there, and – if you’re lucky – their telephone number.

With a name and address, using www.itraceuk.co.uk/Find_Mobile_Telephone_Number.asp, you can find out their mobile phone number. Using www.gov.uk/get-information-about-a-company you can find out the business registration number. Feed that information into www.kompany.co.uk and you can get a registered address of the company.

With a Facebook profile and the endless mine of information that is the internet, you can find out whatever you want to know. Other sites give you the address registration plates are registered to, and others methods that are on the illegal side, but very accessible, can provide you with IP addresses and thus their exact location at different points.

I was able to determine X’s address, phone number, and address of business registration, which was also his father’s residence.

Paparazzi companies have a reputation for doing anything for that money-shot, and from my understanding the one I worked for briefly was no different.

With the information gathered on X from Facebook, I created a new, fictional person. This indemnified me, because there are only laws against impersonating real people. The new identity was an old schoolmate of X, so I added some of his friends on Facebook, and messaged a few to find out how X was doing, whether he was still with his girlfriend – anything which would help me to paint a fuller picture.

I emailed X’s company, as myself, asking whether I could get an internship with them, with the intention of shadowing X. This would allow me to get to know him personally – although I already felt like I knew him pretty well. From speaking to some of his friends I had already worked out that he was an insecure man, the kind of person who amasses his friends, girlfriend, and possessions as social capital. I speculate that he is not faithful to his girlfriend.

The company was reluctant to offer up anyone to shadow, let alone the co-owner of the company, so I had to prove my worth. They knew who I was – my real name, my interest in the culture of paparazzi, as well as what I was studying and where.

We agreed they would add me to their mailing list of celebrities whereabouts. After I got the picture of Tevez – as I mentioned, a sheer fluke – suddenly I got a reply that was interested. They asked me to upload it to the website for them to sell, but instead I emailed it to them with Tevez’s face blurred out. Again, they told me to upload it, so I didn’t reply. They tried to buy the original from me directly. I didn’t reply, again, and by this point it was too late to sell anyway.

A few days later, I emailed to say that I had a picture of Beckham. A similar series of events unfolded.

I played dumb and emphasised that I wasn’t ready for my photographs to be seen publically yet, and I needed to develop my style - I wanted to shadow X. I maintained that with three days of guidance from him I would learn everything I needed to know. I could learn the paparazzi code of conduct, and become a valuable member of the team.

Some examples of the paparazzi code:

The first paparazzi on the site has the choice of positioning,

One must never block another paparazzi’s shot,

One must fully respect all other paparazzi.

The paparazzi business is predicated around a contract between two freelancers. A freelance company hires freelance workers, who in return use the company to sell their commodity. They were, therefore, not able to offer anyone for me to follow. With further sycophancy and persistence, repeated professions of my desire to ‘learn from the best’, I eventually had my three day internship.

I had a few months before it was to begin, though, so I spent the time learning as much as I could about X, whilst explaining I had to focus on my university work – ironically that work was this project. I was able to consolidate my speculation around his insecurity – it was hardly a huge leap of faith considering that he was a representative of a world in which image is everything. I learned that he is the type of person to cultivate himself in a certain image – specifically the alpha-male of ‘lad’ culture. I believed that this was purely affectation, though.

I knew about his friends, where he hangs out, what car he drove, his interests, his character, what he was like at school and what he grew up to be. I wanted to meet him.

One of X’s friends included me in a Facebook Event for weekly (although it looked more like every two months or so) drinks. They were going out for a drink the next day, and I saw that X would be there, and X’s girlfriend was seeing other friends.

The project is about six and a half months along at this point. Prior even to its beginning, I had spent a lot of time talking about the morality of the potential of this project with a close female friends (Y). Along the line we had gone over a lot of the details I had uncovered and speculated together about his infidelity. Y had offered to flirt with X to get his phone number for me and this point came around two months prior to my being invited out for drinks.

The day came around. I went to the bar with Y and waited for around an hour.

They didn’t know what I looked like, but I was nervy. When they came in, Y and I went to the bar to get some drinks, leaving our old ones at our table. We ordered new drinks, and waited for X and his friends to sit down, and sat in the booth next to them. All of them had short, cropped hair, slightly longer on the top, and a mix of chinos and jeans.

When X went to get a drink, Y went to the bar alone. She flirted with him, and quickly they exchanged numbers and parted ways. We left.

When we arrived at my house, X had added Y on Facebook. The next day, he text her.

His messages were very forward and very presumptuous. He made it clear that he ‘only want[ed] a little bit of fun, nothing serious.’ Within two weeks, he was sending very explicit photographs (and in one case, a film) of himself. He suggested meeting up, and I duly accepted.

X said that he would pay for the hotel room, but he couldn’t book it because it would appear on his bank statement, which his girlfriend would see. This was the first time he made reference to a girlfriend, and was quickly forgotten. I booked the room, which was around the corner from Piccadilly Circus Tube Station, in Y‘s name, and everything was set.

Friday 13th, 2013, 19:00.

X was ready. Y's phone was with me. And if X’s texts were anything to go by, he was ready.

I went ahead to the hotel room on the afternoon of the 13th. I placed a copy of that day’s Guardian, as well as a clock, with three GoPro cameras in place.

I waited in the lobby from 18:30. At 19:04, X came in and sat with his back to me. I felt Y’s phone vibrate in my pocket. My stomach churned, but I managed to quell the flinch. I waited 30 seconds, and then got up and asked the man what – as a tourist – I should do with my evening. As I turned around, I could see X on his phone.

I went to the toilet, in a horrible flurry and waited for his message. I waited 5 minutes but nothing. I text him. No reply. I went back into the lobby and looked over at X. My heart beating faster than it ever has before, X looked straight into my eyes.

It wasn’t him.

I sat down and I text him again. I waited 10 minutes with no reply and left.

At 19:58 I got a message from him apologising for his radio silence, telling me that he is waiting for a big celebrity and could not lose this “killing”. He wanted to make it up to me the following weekend. I accepted.

This project had been causing a lot of problems internally for me at university. Discussions - and arguments - about the ethics and morality of what I was doing, and this latest development had got to a point where it was made clear to me that this project needed to end immediately. Later that day I text X that I would no longer be communicating with him anymore.

This project had always been building towards an exhibition and although my university would not allow this to be marked, I organised it nonetheless. X was invited to a private view.

The invite was sent to his home address, stating that there is an exhibition about the culture of paparazzi, and that he was to be the - paid - guest of honour, if he agreed. It was made clear to him that there were to be no plus-ones. He RSPV-ed.

The exhibition was just for him, there were to be no other viewers, it was a private-private view.

As X arrived and opened the door, I sat in a concealed annex to the gallery. I heard him laughing at the camera flashes, which flash as the door opens.

From then on, there was no laughter. In vinyl on the wall as he turned the corner were the words “I hope they get my good side.” (in one of my emails, I asked him the most important question I would ask him, “How would you feel if you were being paparazzied?”

Y’s phone was there, a laptop with her Facebook account was open, with all of the conversations he had with her. Photographs from the night they met. All of the photos he had sent to her - with the date and timestamp of when he sent them, - in all of their explicit glory, were on the wall for him to see. Photographs of me with his dog, fiancé, and his friends were also on display. The quiet audio in the room was a playlist of phone conversation I had with X’s dad.

I came out.

We had a relatively short conversation, considering all of the above. This conversation will remain between the two of us. I gave him the password for Y’s Facebook account, which he deactivated. I gave him the hard drive with all of the footage and audio on it. He has Y’s phone, and all digital records of it. It was never made public, and nor shall it ever be. It never happened.

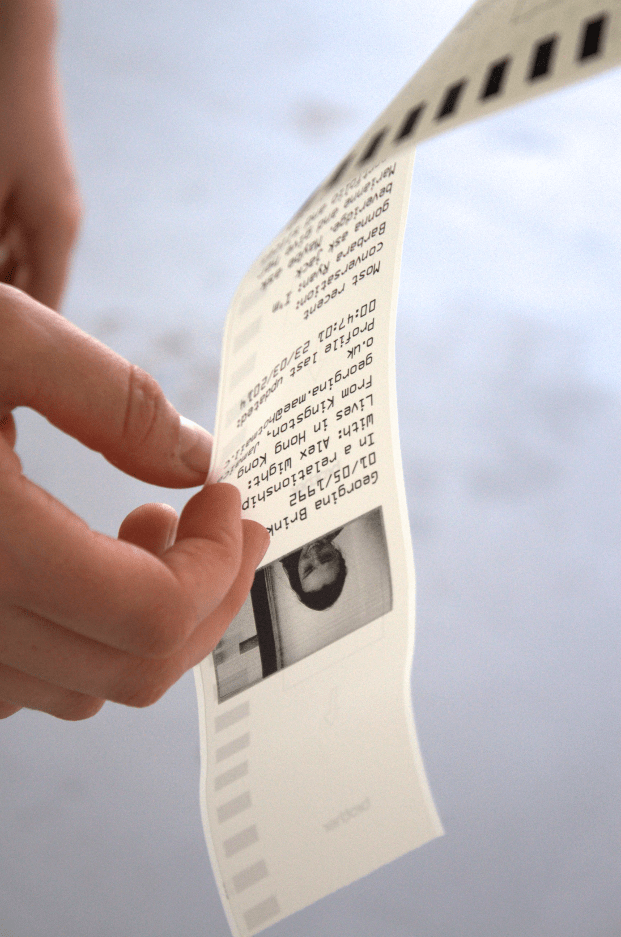

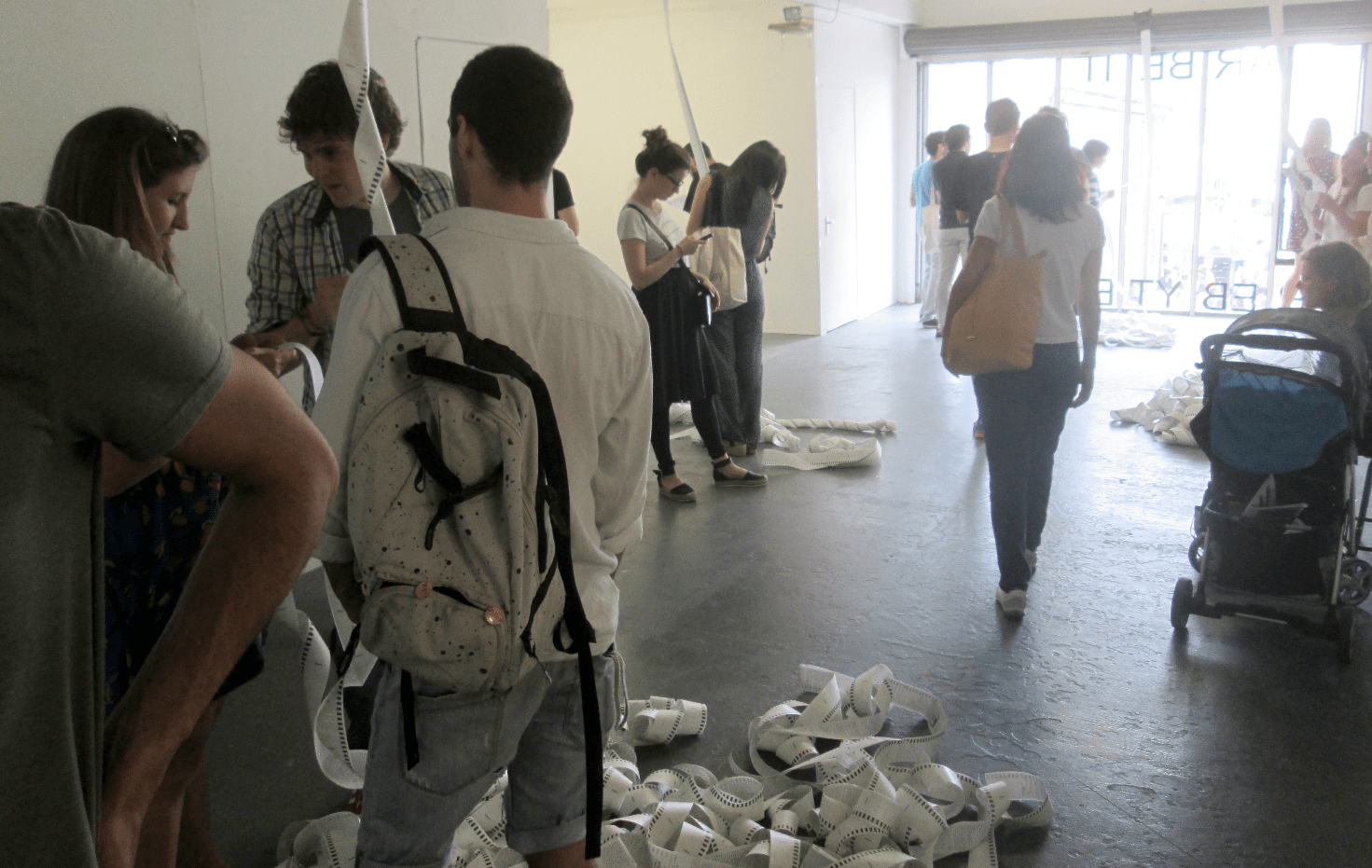

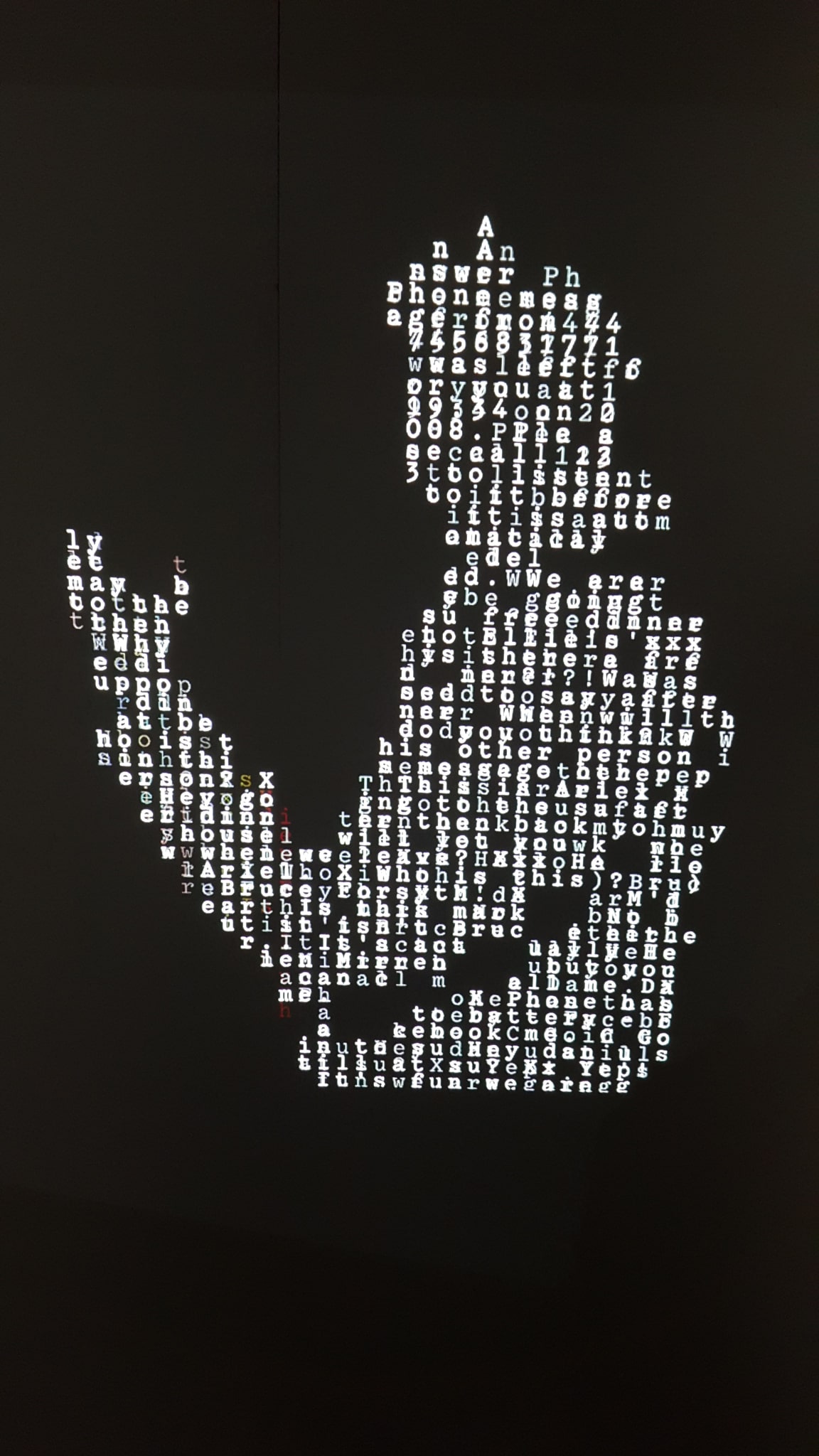

Data Shadow (2015)

Only when something is published does it become real.

If we take ‘privacy’ as a state in which one is not observed or disturbed by other people, and ‘anonymity’ as a state in which one is unidentifiable, then we have to understand that the ‘privacy’ and ‘anonymity’ we are presented with are illusions. As the levels of data collected on the individual continue to grow and be legally shared, the illusion can only become more fragile.

Privacy is an important social right because it ensures that one’s validation comes from within, and ensures that one can live freely and without judgement. This self-validation has historically taken place when one is anonymous - no matter how briefly - from society. However, technology now intrudes into this space, meaning that we are never truly alone. Moreover, many of these new technologies are predicated around individually tailored algorithms which, instantaneous and uninvited, feed our desire for further information, simultaneously giving us a sense of empowerment, accomplishment, and fulfilment. We respond to this means of communication as it allows for almost total, unbridled connection at all times, and allows for our memories to be documented, and allows us a new window on the world.

We don’t see ourselves through our emails, text messages, or phone calls, but the recipient can and often does. We know the majority of those we would call our friends through their texts, phone calls and social media accounts – the technology becomes a veil between us and the world. We represent how we want to be seen or heard through technology. Viewing others in the restrictive structure which the Internet has brought with it papers over the cracks of our insecurities, focusing on socially positive aspects of one’s life and interests. This is not to question whether this is in aggregate a positive or negative thing, but rather – when something becomes so personal – whether embodying the individual in details probably unknown to the individual themselves, requires tighter government regulation of the data being collected, assessed, and sold, in order to protect the individual.

Below is a (by no means exhaustive) list of some of the information that is easily accessible:

Locations – our physical whereabouts at all times when our phone (or laptop) is in our presences

Photographs – our memories and reference points - time and location

Searches – most often used to find out facts about our conversations - time and location

Phone calls – caller, duration and location of call

Music – emotion, routine and character type - song, time and location

App usage – Tinder, Grindr, likes, dislikes, and success rates

Online purchase history – physical location and buying habits

When you start combining these pieces of information, one is able to paint a fairly detailed portrait of an individual. As much as anything, the information could be used to determine: your wealth; the places you visit and your routine based on this use of location tracking; and detail around when you are likely to be home, useful to the potential burglar.

A discussion needs to be had around the levels of responsibility the government has to protect the individual. Advertisers are the most publicly visible manifestation of the growth in data mining, and are commonly sold much of the above information. Click on Amazon, and view a book, then load up Facebook and you’ll likely see the book advertised there. This usually happens in the space of 0.01 seconds, and has over 3 billion potential targets worldwide. The two most valuable companies in the world are Apple, with an estimated worth of $720bn, and Alphabet (the parent company of Google), at around $500bn (figures correct as of June 2015).

In the new digital age, individuals have become the commodity and personal data is the currency. In the commodification of the individual, clicks, engagement and interest has become the payment. The phrase ‘time equals money’ has never been more appropriate than in the new digital age, which has brought with it the purest form of Capitalism, which is barely regulated by government, and in which globalisation, total privatisation and monopolisation (by companies such as Google, Amazon, and Facebook) rule the conglomerate.

The Internet brings with it many things: connectivity, safety, education, exploration, and unprecedented acceleration in the growth of medical research. As well as this, an increase in national and international interaction unity, and unfathomable social phenomena. Everything which allows society to grow and come together is available, while still allowing a platform for individual voices.

One’s perception of oneself, as well as of others with who interact with the platform with a digital avatar, be it through Facebook, Twitter, or even more basic telecommunication, gives a sense of empowerment. However, this feeling of empowerment is a false one, and only very rarely are we actually heard.

Localised misconception of empowerment being confused with true empowerment, is a misconception the government actively cultivates and maintains, as was made clear in 2013 when The Guardian, The New York Times, and Der Spiedel leaked some of the documents Edward Snowden copied.

This was not the first time the illusion of privacy and anonymity had come under attack by the media: in 2001 William Binney, a former US National Security Agency (NSA) Technical Adviser and employee for 32 years, blew the whistle on the removal of safeguards on a programme called ThinThread, which would allow US Citizens’ data to be monitored by the government. In 2011 Casper Bowden, a former Microsoft manager who warned the governments of 40 European governments that if they used Microsoft based Cloud storage systems then their information would be passed onto a surveillance operation called PRISM.

PRISM enables the US Government to capture the private data of citizens who are not suspected of any connection to terrorism or any wrongdoing to individuals of major Internet services like Gmail, Facebook, Microsoft, and others. It’s was one of many of the US government’s post-9/11 electronic surveillance efforts, which began under President Bush with the Patriot Act, and expanded to include the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), enacted in 2006 and 2007.

It wasn’t until 2013 that the methods and reality of the operations of the NSA and the UK Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) became clear. The level to which the NSA have legal permission to access sensitive information is not limited to that of the individuals under – FISA – the NSA intercepted over 125 different forms of Angela Merkel’s communication lines and 98% of Latin America’s communications which passed through their servers, as well as human rights charity, Amnesty International’s private conversations.

FISA was introduced in America by Richard Nixon in 1978, in order to allow the president to spend political resources to spy on potential political and activists groups without the need for Judicial and Congressional courts, as well as physically and electronically collect ‘foreign intelligence information’ between 'foreign powers'.

(a) “Foreign power” means—

(1) a foreign government or any component thereof, whether or not recognized by the United States;

(2) a faction of a foreign nation or nations, not substantially composed of United States persons;

(3) an entity that is openly acknowledged by a foreign government or governments to be directed and controlled by such foreign government or governments;

(4) a group engaged in international terrorism or activities in preparation therefor;

(5) a foreign-based political organization, not substantially composed of United States persons;

(6) an entity that is directed and controlled by a foreign government or governments; or

(7) an entity not substantially composed of United States persons that is engaged in the international proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.

To contextualise FISA, this act was introduced in 1978, during the cold war, thirteen years before Tim Berners Lee built the first website in 1991. The FISA Amendments Act of 2008 passed through Congress, combining three key elements:

(1) The first stated this law only applies to; ‘citizens outside the US’; roughly 95% of the human population, meaning a ‘warrant is not required’ for access.

(2) The second, largely overlooked at the time, was that access would be granted to remote computer services – essentially what we would call Cloud Computing.

(3) The third and most importantly makes clear that ‘criminality’ and ‘national security', are not necessities for access.

This discrimination against anyone who is not American fundamentally contravenes the European Human Rights Act. Human Rights are universal, and included among them is the right to ‘privacy’ – if the state is justified in infringing the individual’s right to privacy by way of surveillance, then it follows that the ‘justification has to remain objective’. That is to say that it must relate to an individual’s actual or potential actions, not reduced to nationality.

The 4th Amendment reads: ‘the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.’

After the American Revolution (1775-1783), the 4th Amendment was introduced to counter the frequent British abuse of the powers of ‘General Warrants’. A General Warrant allowed a British Redcoat access to the home of any American Protest Revolutionary, and the right to seize anything from weapons to alcohol. It essentially allowed for British intrusion into any home, whenever it was convenient, and as a result the 4th Amendment was introduced in 1792 by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson (the 3rd President of the United States, 1801-1809) and US House Representative James Maddison (4th President of the United States, 1809-1817). As a result, it has remained a vital cornerstone of the constitution upon which American notions of Human Rights are largely based, borne out of a very real, but very distant and separate threat to privacy than the ones which the American public have faced in the centuries since, no longer at the mercy of the British but of their own governments.

After the leaks of 2013, Congress discussed whether the 4th Amendment applied to non-US citizens. The conclusion reached was that a warrant was not required to intercept and decipher personal information, be it text messages, searches, locations, or anything transmitted electronically. In simple terms: if you are not American or physically in residence in America, and your information is sent through American servers, you have no rights whatsoever to the privacy of the data you amass and use.

The European Human Rights Law, which includes the right to privacy, applies to European and non-European residents, and is intended as a universal and objective law. However, US-based Apple, Microsoft, Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Tinder allow the US government blanket access to our data, which is in turn is passed on to GCHQ and the German Federal Intelligence Service (BND).

As we move further towards cloud-based storage, due to its economy, convenience, and perceived security, every aspect of the individual’s life is being collected and analysed. What we find as with any new and exciting media is that it becomes increasingly consolidated, closed, and dominated by monopoly or oligopoly. History shows us that monopolies are powerful tools for governments, as they can be used to serve political ends.

But:

‘They’d never look at my information.’

Reports say that police have a 93% success rate when requesting access to private mobile phone and email records, with a request being lodged on average every two minutes in the United Kingdom – 670 successful requests per day.

Still:

‘I have nothing to hide.’

History also teaches us that power corrupts. As this power becomes more insidious and absolute with technological revolution, will history repeat itself, or finally prove to be archaic?

Poisonous Antidote (2016)

Without social media you become forgotten.

We are regularly told that if we do not agree to the terms and conditions of a service online, we have the choice not to use it. Apple? Google? Facebook? They pretty much all say the same, and that, in essence, is that they own every piece of data, including the account, and they can do whatever they please with both.

In October 2015, in conjunction with my exhibition Data Shadow, I gave a talk at the University of Cambridge’s Festival of Ideas, titled "Anonymity is our only right, and that is why it must be destroyed". At the end of the talk, I shared all my login details with the audience. This included all my personal and professional email addresses, my Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn profiles, my Apple ID, and my (closed) online banking details.

My intention was to live without a digital footprint for 6 months, and since I didn’t ever own the accounts, giving away my passwords was the only way I could think of "deleting" them. Just as writing over a note a few times before throwing it away makes it harder to read, anyone who was, or is using my accounts (as continues to be the case with Twitter’s @markfarid) helped write and associate new and incorrect data to a supposed Mark Farid.

Having relinquished all my passwords and login details, I spent the first two weeks without a phone or computer, and for the remaining five and a half months I used three laptops at specific times and places, which, through IP spoofing, firewalls and various other techniques, made my digital footprint harder to track. I had different pay-as-you-go phones, which I would replace, along with the sim card, every month. Any accounts I needed to make were linked to different individual, unlinked pay-as-you-go sim cards. I changed my bank accounts and paid for everything in cash. I bought daily travel cards and attempted to live life as normal.

What proved very apparent very quickly is that as a 23/24 year old living in London, there is no real choice over the usage of many digital and online platforms, let alone the choice of using a computer or mobile phone. Without them, my social, cultural, and financial life – and I’d go so far as to say my mental stability – were all affected in negative ways.

When I was with people, connections might have been ever so slightly deeper, but they still had smartphones. And when I wasn’t with people, I became very aware of how alone I was – although I now know myself and what I want from life much more as a result.

The hardest aspect of all was, undoubtedly, the cultural isolation. Though I maintained the ability to go on websites, my news and cultural references became increasingly exclusive, gradually growing more specific and narrow. The nuances of culture, of humour, and wit became impossible to maintain, limiting my capacity to interact with others.

Life is not only much simpler when we just click “yes”, but happier too. We are able to build stronger relationships with family, friends, and partners, not regulated by physical distance. You know what is happening in the world, in culture, and you know where you fit into it.

This connectivity with people has brought unprecedented levels of safety and education, as well as advances in medical research and treatments. Social media has brought with it 24-hour access to friends, family and foes alike. The tailored news feeds (algorithms) we use continue to unite individuals and groups with common interests, humour and cultural phenomenons.

As the 21st century demands ever-increasing efficiency in the conduct of our lives, having a standardised platform on which to judge people is undeniably pragmatic. But it also allows us to see ourselves as others see us, giving our projected-self – a constructed image of who we want to be – a dedicated space to exist. We can play up, censor, and edit ourselves more easily, and we can do so over time, fashioning and reforming an image we are happy with.

Knowing that everything you do is digitally documented allows you to judge yourself more easily at the price of being dependent on the categoric "reactions" of one's peers. And when our self-fulfilment derives from the number of "likes" this projected image amasses, our social conduct on all platforms (including "real life") is increasingly driven by the needs of that image.

That is why Poisonous Antidote saw me broadcast all of my personal and professional emails, text messages, Skype and Facebook chats, web browsing, phone calls, and Twitter and Instagram feeds. All pictures and videos I took appeared in real-time, along with my phones’ locations which were updated every 20 minutes. In addition, (some) adverts generated by websites I visited were broadcast (www.poisonous-antidote.com).

The project ran from September 1st to September 30th 2016. For the first fifteen days, I found my usage of my phone and laptop were normal. If I consciously acknowledged a change, it was, if anything, that I gained in confidence – using the experience opportunely to send things I might otherwise have not. But on September 15th I made a Facebook and a Twitter account, and almost immediately I became aware, even anxious, about some of my prior arrogance. The people on the other side of my communications, as a whole, interact with me as usual.

Progressively more changes occurred. When I would wake up, my phone and computer were not the first things I looked at, as I didn’t want people to know what time I woke up. When I did eventually go on the Internet, check my emails or reply to messages, the first thing I looked at was the news, not the Leicester Mercury to read about football. When I was working, I didn’t procrastinate, because everyone could see that I was procrastinating. I became very aware of my locations, so I ensured that I was going out, that I was sociable, and that people could see I was being productive with my time. I spoke to my family more, seeing them more than average – despite them living in Leicester. I was on the Internet less, I was more productive, and I was enjoying myself more.

I still struggle to draw conclusive judgments from this project, but it has certainly highlighted my own online editorial habits, the density of our digital footprints, and, for me, the necessity of privacy. Unlike Data Shadow, where I gave up online privacy to gain personal privacy, only to realise social media is indispensable to contemporary life, Poisonous Antidote embraces the publicity of social media. Subsequently, I have found that I was consciously and subconsciously changing my actions and behaviour to ensure I conform to society’s ideologies – that I was doing what I’m "meant" to be and feeling validated by the knowledge people could see this. I was constantly judging my actions and options through the potential reception of my newsfeed, assessing my and their adherence to a standardised code of conduct which allowed a form of acknowledgment that confirms my actions and behaviours.

As we continue to give up more and more personal data, government’s are gaining further legal access to it. In June 2016, 444 MPs voted in favour of the Investigatory Powers Bill (the so-called Snooper's Charter), opposed by just 69 MPs, indicative that the general public no longer value privacy as a protected right. But if we take the OED’s definition of "privacy" as a state in which one is not observed or disturbed by other people, and "anonymity" as a state in which one is unidentifiable, privacy and anonymity are fundamental social rights, for they ensure one’s validation comes from within. Without the fear of social reprisal, one can live instinctively, protecting the self-validation that is innate to individuality.

Without privacy, our social, political and cultural freedom is compromised, impeding variety and our potential scope for learning. Freedom of speech is destroyed as freedom of thought is eroded.

Economically, collating my digital footprint – as Poisonous Antidote did – into one newsfeed of emails, phone calls, photographs etc. is highly efficient. But in doing so, it also plays to my online persona. The validation and fulfilment I felt when I went out in the evening for a few hours, wherever it was, knowing I appeared to be socialising to the outside observer, placed my virtual-self at the centre of my real-world experiences.

The validation that Poisonous Antidote created can only be fulfilled by further consumption, and as I used it more, each post, action and interaction meant less, for I became more reliant on it to fill the growing void it created. It becomes a self-feeding machine, self-validating machine; a drug.

Publishing every part of my online activity might appear to represent some dystopian future. But the truth is that most of us are doing exactly this right now, all the time – albeit in a more limited way. We are constantly self-publishing the details of our lives to technology companies, to governments, and to our networks on social media. The difference between you and I is of degree, not kind.

In a world where we auto-publicise our digital footprint 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, I can’t see how something fundamental won’t change in the human psyche. We are becoming subconsciously habituated to the potential of not only being watched, but held accountable at any time by family, friends and governments. While humans have always been conscious of the judgement of our peers, the amount and the depth of information we now give them is unprecedented in human history.

When humanity transitions to an epoch in which every waking moment of an individual’s life is auto-publicised without cursory thought given even to the concept of privacy, there is going to be an indelible effect on the human psyche. We understand and shape the world in our distinctive image, and our individuality becomes eroded with our ever hegemonised and ever-globalised cultural identity. Our identities and behaviours are stored publicly and permanently, allowing only for conformity to political, social and philosophical ideals, norms and thought processes.

As technology continues to invade our personal lives, our privacy and, in turn, true individuality is replaced by a hegemonised and globalised cultural identity. We are encouraged to conform to political, social and philosophical ideals, with our identities and behaviours stored publicly and permanently, leaving individuality to exist only within the shadows of conformity.

seeing i (2015)

We assume the physical world is natural.

One of the greatest limitations on human beings has always been the restriction of civil liberties. These are normally determined by financial and social wealth. We see this in every country on the planet, capitalist or not. We are born into the world totally dependent on our parents, and necessarily dependent on the development of our understanding of the structure and format of language, relationships, education, societal relationship, and ultimately our expectation of life.

What we collectively deem to be socially acceptable, that is to say cultural and legal norms, is the main influence of people’s conduct and moral beliefs. Historically, the moral and ethical code of law has been dictated by the establishment, but over the last 100 years, namely with the influence of the media and unions, there has been a shift towards the converse, a state in which what we, the collective of individuals, deem to be socially acceptable feeds into the law, most notably when it comes to Rights. We see this in growing women’s rights and in the legal and social ramifications of racial and sexual prejudice. Laws enable rights - the core of any code of rights is the limitations and restrictions placed on attitudes and behaviours. Rights offer privilege, gratitude, and the perception of autonomy in the potential of legal reform. Legal reform, of course, is the renegotiation and with the hope of loosening small restrictions on rights.

We learn the concept of rights and how we must interact with one another from our parents and those around us at an early age. In school, we are taught the value of history, competition, and the structure through which we will deem ourselves to be a success or failure. We go to school from the age of 4 to 18 (in the United Kingdom), and during those years we are also taught that maths, language, and science are incredibly important and that to succeed in these areas is tantamount to individual fulfilment. Our grades are standardised, so that we must ‘beat’ our peers in order to succeed – we measure our success through the failure of others. Conflictingly, we are also taught that deep-rooted competitiveness is a negative trait, and to live our life by a deeply philosophical ideology which governs the entirety of our lives. Only those with the best education (omitting some high profile examples of those with a less successful education) and grades achieve what we are all taught to desire and to measure as success: financial security, happiness, and social validation. The system is fundamentally built to ensure that unless you conform to this structure you cannot ‘succeed’.

The expectations we have of life are dictated by how we measure success. A male born into a working class family in China has a very different set of societal ideologies than that of a woman born into a Saudi Arabian family, or a white, middle-class male born in the United Kingdom. All societies use a similar structure predicated around free trade to ensure that wealth remains fixed and unequally distributed. As the rigidity of social inequality is firmed, philosophical discourse is confused with success and individualism.

To use an extreme highlight to emphasis this point, on 4th August 2011, a 29 year old black man named Mark Duggan was shot and killed by police as a result of allegations of terrorism. Protests were held in Tottenham Hale, North London, and by 6th August thousands of people rioted across London and England. The resulting chaos generated looting, arson, and the mass deployment of police. Several violent clashes ensued, and police vehicles, double decker buses, and businesses across the country were destroyed.

By 15th August, the riots had essentially come to a close, and over 3900 arrests had been made, with 2298 people prosecuted for theft, 885 for disorder, and 67 for arson. There were five deaths, and at least 16 injuries, and an estimated £200 million worth of property damage was incurred, not to mention a significant compromise of local and national economic activity.

Political and ideological protest at the unjust murder of a young black man - via collective individual power - was turned into material avarice, and instant self-gratification which we are taught to strive for in modern Britain. London lost sight of its motives, and instead wrought havoc in pursuit of the new 40 inch Sony TV or Air Max 1 trainers which we’re repeatedly told will make us happy. The civil distress has resulted in the purchase of water cannons and rubber bullets by Mayor of London, Boris Johnson with taxpayers’ money at the cost of £218,205, against Parliament’s wishes, as a means of ensuring future autonomy.

Boris Johnson in 2015 talking to Theresea May, Home Secretary, in Parliament, London: “We can’t use them [water cannons] at the moment. We haven’t been given a general licence for their use. We will keep these devices in reserve and should there be another occasion when they might be a useful tool of crowd control, the Metropolitan police commissioner can make another application.”

The structure of protest as a means of displaying dissent exists and is permitted by the government, as long as 6 days’ notice is given and a route and timescale is published. What should be a pro-active, self-validating and important civil action appears to be an illusion of empowerment. One must ask: what options are available to the public once protests have been completed and ultimately ignored? Riots are protests, borne in frustration at the decisions and behaviour of those who hold governance and a lack of alternate recourse. Protests, and this kind of action, allow the public a vent for frustration, a show of self-worth, however when it is rooted in genuine emotion by enough collective of - generally speaking work-class individuals - riots emerge due to alternative options, at which point frustration becomes aggression which in turn becomes about individual gain and material value.

It is clear that this frustration was not one which gestated and grew over the course of the London Riots in 2011, rather the looting began almost instantly, on the 6th August. The need for material luxury was already well fixed in the minds of the frustrated, and reared its head almost as soon as the opportunity was presented. Once we’re past the wealth necessitated by society – accommodation, food, bills – we still want more.

The appearance of wealth is key, because wealth is a signifier of success, and to show its validation – the restaurants you can afford to eat at is a gesture, just as your hobbies, interests and choice in your professional and personal life.

Individuality is evident to a degree in the choices we make with our money, but the choice whether to make this show of affluence is one made by society, and by the time we have the money to show off, we are so used to having been funnelled through certain decidedly limited life choices which have been instrumental in deciding where we are at certain points. At the age of 14 in the UK, we decide what GCSEs we are going to take, and thus begin determining our futures. We are presented with choices tailored to standardised individual tastes.

The physical structure of the world we live in is no different. We all live in square boxes, we look out of our window and see square gardens. Every building, road, park, and field has been designed. Trees are planted with express goals, pertaining to aesthetics, ecology, and positioning. Every sound; creak of a floor board, every church bell we hear ringing, engine revving – they have all been engineered. Nothing we exist in is natural: even the sound and feeling of the wind we experience is influenced by the man-made surroundings it passes through.

The illusion of autonomy presented to us is in simple, unimportant choices. What clothes to buy. What pre-existing job we join. Which football team we support. We take for granted that 21st Century Britain is domesticated and forget how unnatural that is. We submerge ourselves in manufactured sight, smell, sound and touch; We all live in square boxes. We look out of our windows and see square gardens. Every building, road, park, and field has been designed. Trees are planted with express goals, pertaining to aesthetics, ecology, and positioning. Every sound – creak of a floor board, church bell, engine revving – has been engineered. Nothing we exist in is natural; even the sound and feeling of the wind we experience is influenced by the man-made surroundings it passes through, and this is before we think of the influence of man on the climate itself.

This synthetic experience we have of life is entirely dependent on our senses. Imagine a world in which we have no senses, in which we are deprived of sensation and unaware of our surroundings, numb to the world and numb to the fact that our experiences are engineered and fictional. We believe that this fiction is truth because it is the only knowledge we have. We assume that the physical world is the ‘real’ world, and at this point simulation becomes life. We are standing in Plato’s cave, facing the walls and naming shadows, believing that this is it, oblivious to the fire outside.

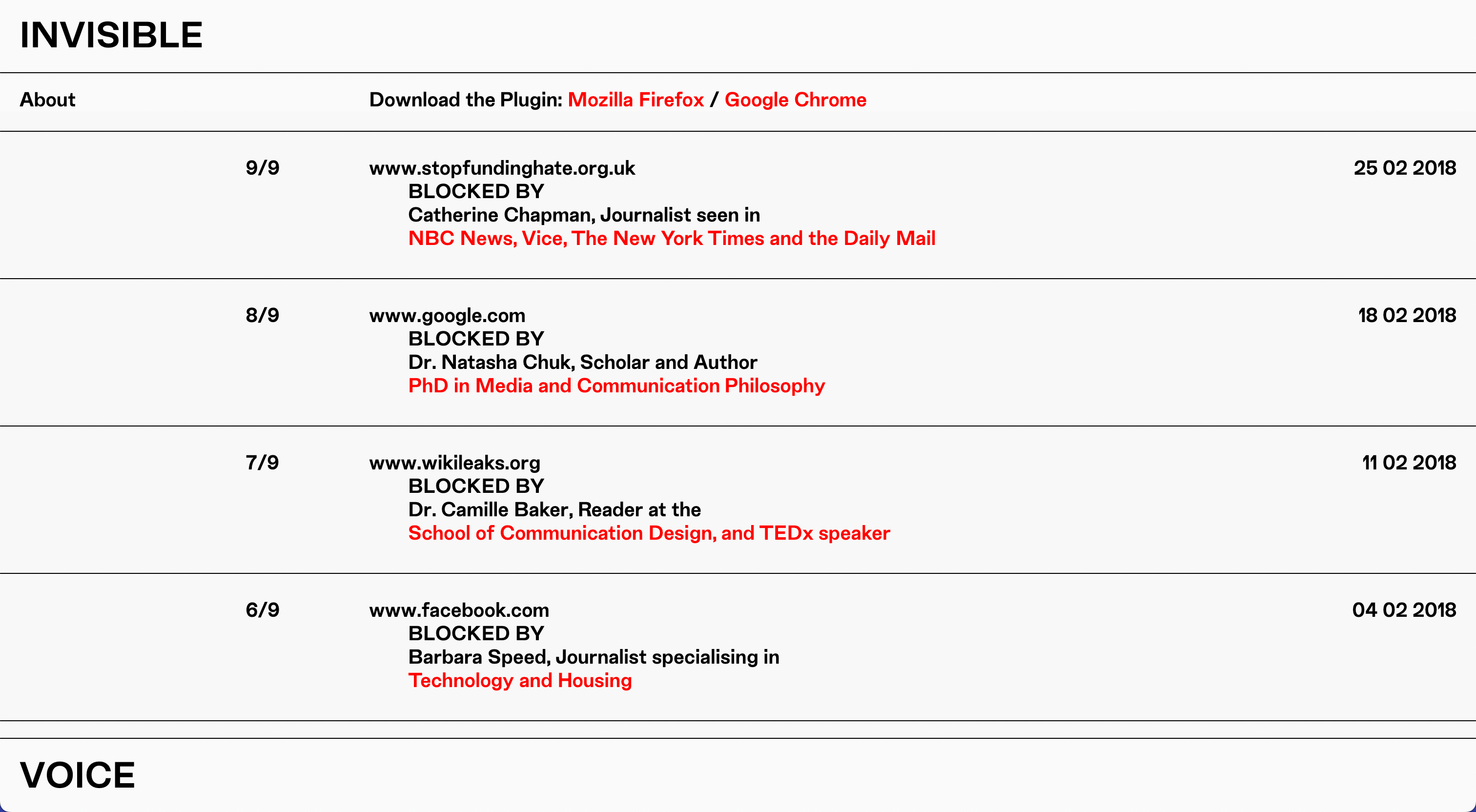

Invisible Voice #1 (2017)

There are profound consequences if the chicken comes before the egg.

Individual knowledge, that is cultivated privately and never spread, exists purely for the individual. Only extremely rarely will it have any impact or reality on a collective of individuals. ‘The main means of mass communication’ – the media – exists to explain to the collective of individuals events which have happened, but also those which are yet to take place.

Consumption of media has always been a somewhat solitary exercise – newspapers were not intended to be shared, more likely thrown away after having been paid for. Then, the introduction of the radio in the 1920s brought the media directly into the home, cementing the transition from an experience shared with others to a more individual, private experience. We more and more regularly consume media alone, through once analogue and now digital mediators – as such, our consumption of politics, culture, and entertainment has become an isolated experience, existing between us and the media.

The media gives us context, highlighting not only our own social classes but the functions of society in the wider world. Cultural influences, like art or film, have social influence; they teach us what is ‘cool’, how to interact with people, and even how to seduce partners. Political influences, like the news, allow us a perceived empowerment, giving the illusion of cultivating cultural and political awareness, and a sense that we have independently come to conclusions autonomously. This is a false perception. To acknowledge the authority and respect the media commands over the individual is vital.

The responsibility of the free press is to ensure that a respect for the diversity of morals exists; to give voice to minorities and disparate cultures; and, crucially, to hold politics and politicians accountable. The press is a defender of civil liberties and a challenger of the status quo; it is vital that the press remains free. According to the RSF World Press Freedom Index), in July 2016 the UK had the 38th freest press out of 180 countries, whereas the USA had the 41st, compared to 34th and 49th respectively in 2015.

However, in constantly challenging and pushing boundaries, the press also set the parameters and restrictions on what is culturally, socially, and morally acceptable. It chooses who and what to question, and it decides what we will be aware of. Fundamentally, it influences our decision-making, morality, and way of life by setting the limits on norms.

‘Life in the United Kingdom: A Journey to Citizenship’, Edition 2, 2011, is one of the required readings to claim citizenship in the UK. In it are the words of the Home Office: ‘The UK has a free press, meaning that what is written in newspapers is free from government control. Newspaper owners and editors hold strong political opinions and run campaigns to try and influence government policy and public opinion. As a result it is sometimes difficult to distinguish fact from opinion in newspaper coverage.’

In much the same way as a text can shed and change meaning in different contexts, the imagery, phrasing and framing of shots deliberately manufactures misinterpretation. To use an extreme example to highlight this, on 17th April 2015, writing for The Sun newspaper, Katie Hopkins wrote: ‘what we need are gunships sending these boats [Syrian refugees] back to their own country.’ Five months later, on 2nd September, Katie Hopkins wrote in the same newspaper: ‘today The Sun urges David Cameron to help those in a life-and-death struggle not of their making,’ attaching an image of a Syrian child who had drowned. This image alone emphasises the power of relatable imagery – the British population were swayed in the favour of allowing 20,000 Syrian refugees asylum in Britain by 2020.

In practice the free press distributes information with very little accountability - Rebekah Brooks was arrested and suspended as CEO of ‘News International’ as a result of the phone hacking scandal in 2011, but since 2015 she has been the CEO of ‘News UK’, which amounts to little more than the renaming of the original organisation. Meanwhile, the individual absorbs the media’s information often unquestioningly, rarely speaking about it.

Our relationship with political media tells us what we ‘need’ to know. To paraphrase Donald Rumsfeld – there are things we know, there are things we don’t know, and there are things we don’t know we don’t know. To decide that there is information to which the individual should not be privy is to remove autonomy from not only the individual, but from the collective of individuals who determine their actions and behaviours based on the limited information provided.”

The potential for the narrative of the reportage we are accustomed to in 2016 and 2017 to become fictionalised seems to be growing. The British people’s decision to leave the EU under false promises of £350 million a week being directed to the NHS, and Donald Trump’s progression from the media’s villainous jester to the most powerful man in the world are indicative of the real-world repercussions of the media’s spotlight. Journalists and organisations who report false and speculative headlines seem not to be held to account; ‘clickbait’ (headline grabbing stories) takes precedence and there is no acknowledgement that the media giving attention to these stories, whether in a positive or negative light, gives them credibility.

In determining our perspective, the media decide our future, as their proleptic visions become reality. We don’t own the news, in much the same way as we don’t own our history – it becomes part of the collective record.